Noise, Nightmares, Panic Attacks: When Bitcoin Miners Move Next Door

Amid mounting backlash, is Paraguay’s crypto boom going bust?

For the last six months, residents of Barrio Santa Lucía, Villarrica, have been living 24/7 with a piercing, high-pitched and “unbearable” hum.

“It was a distressing noise that left me feeling powerless”, says María Sol Arrúa Ayala, a lawyer who works as the cultural secretary to Villarrica’s municipal government. “It was like being inside a washing machine.”

Locals spent weeks puzzling over where the noise was coming from — until they identified the source. It felt like they were “facing an alien, with guards and guns,” Arrúa adds, “a giant in the neighbourhood.”

This is life next to a cryptocurrency mine: a warehouse, typically hidden behind the high walls of a compound, containing thousands of energy-intensive computers specifically designed to generate Bitcoin and other digital currencies. It’s an industry which, in barely a decade, has exploded in hydropower-rich Paraguay.

And the once-sleepy town of Villarrica has found itself the epicentre of this high-tech mining boom. It boasts cut-price power, thanks to a historical arrangement between local energy firm CLYFSA and ANDE, Paraguay’s state electricity provider.

But there’s a downside: massive bitcoin mines, popularly known as granjas or farms, popping up metres from people’s homes.

Crypto farms are surprisingly noisy. Industrial-sized fans are used to cool down the whirring machines, which would otherwise overheat in the 40-degree Paraguayan summer.

And some mining operations in Paraguay — like their counterparts in the United States — have started to rack up a litany of health complaints.

Arrúa describes numerous impacts on her family. Ringing ears, stress-induced nightmares, sleep deprivation: even panic attacks from the constant buzzing.

“Some local children with autism couldn’t leave their homes,” she adds. A friend came to stay: after three days, her ears started to bleed.

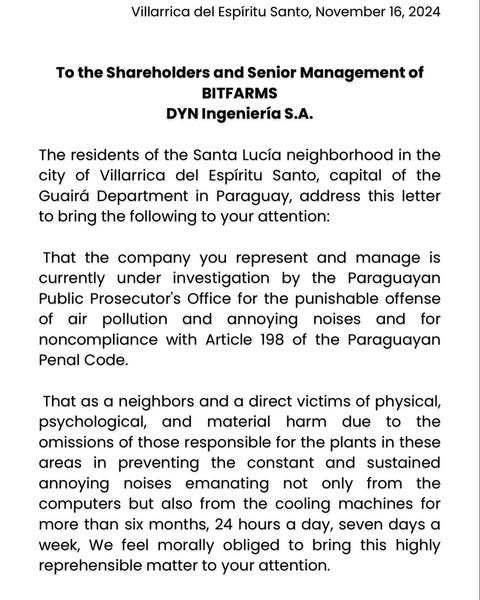

Worst of all: Arrúa and her disgruntled neighbours could find no way to raise their complaints with the Canadian-headquartered firm that owns the mine.

Villarrica’s Environmental Department reported noise levels of 75 decibels — well above the 60-decibel limit permitted at night-time. In October, mediation was held between residents demanding “zero noise” and the mine, but didn’t get far.

Exhausted Villarriqueños turned to social media. With scrutiny mounting, in November the local public prosecutor’s office launched an ongoing criminal investigation for noise pollution.

Two weeks later, the mine made technical adjustments, bringing some peace back to the neighbourhood: at least for now.

Sparking opposition

As crypto hype sweeps the world, with one bitcoin currently trading at US$100,000, the dispute in Villarrica illustrates the industry’s potential pitfalls.

It’s also a symptom of a gathering backlash against the bitcoin business in Paraguay.

The country was once talked about as a Mecca for miners thanks to its surplus of cheap, clean electricity from the Itaipu dam, low taxes and light-touch regulation. Miners were invited to sign bespoke contracts with ANDE according to their energy needs.

Cryptocurrency miners, by some industry estimates, now use 600MW of Paraguay’s electricity supply: fully 25% of the country’s half of the output of Itaipu.

Yet in June, in an apparent crackdown on the industry, ANDE raised its energy tariffs for formal bitcoin miners by up to 16%. Officials bust down doors to rural compounds and even an evangelical church housing clandestine operators irregularly hooked up to the grid.

Under an updated penal code, miners caught stealing electricity from ANDE can now get 10 years behind bars. Ordinary citizens are being encouraged to report any suspicious-looking connections.

Meanwhile, the policy environment is uncertain. A flood of controversial bills were tabled in congress throughout 2024: some trying to regularise the industry, others to strangle it. Little coherent public conversation about the industry, and whether it’s the best use of Paraguay’s fast-diminishing energy surplus, has ensued.

Many projects have stalled while cryptosaurios — to adapt the term coined by Tomás Palau, empresaurios, to refer to the dinosaur-like figures straddling business, politics and organised crime in post-Stroessner Paraguay — lobby behind the scenes to swing regulation their way.

This legal grey area has made it hard for legitimate businesses, instead favoring those with cash, political influence and know-how. A black market in used mining equipment is meanwhile flourishing via WhatsApp groups.

The big players are still thriving. Most of the industry’s energy consumption goes to a few (mainly foreign) companies with contracts of over 100MW. These saw the smallest tariff hikes last year, allowing heavyweights like Nasdaq-listed HIVE to double down with multi-year investments in data centers and infrastructure.

From paradise to exodus?

Patience among smaller outfits has run thin. Many crypto cowboys talk about heading to Brazil or Javier Milei’s Argentina in search of greater stability and profits. Industry association CAPAMAD claims Paraguay would lose out on $1.4 billion in investment, as well as jobs and tax receipts, were all the country’s miners to jump ship.

Paradoxically, some members of Peña’s government profess a pro-bitcoin strategy.

“How good would it be if we did the smart thing and gave the energy to cryptominers?” asked industry minister Javier Giménez in an interview in June. Bitcoiners, he suggested, could make profitable use of Paraguay’s spare energy for now, while the country prepares for industries “of the kind we like”.

What those industries are remains unclear. Giménez may have in mind investors like ATOME, whose 145MW “green” hydrogen facility near Villeta is due to break ground in 2025, or pulp giant Paracel, which says it will bring 40,000 jobs to Concepción by the time it gets going in 2027.

The entire mining industry has fewer than 400 workers registered with Paraguay’s Instituto de Previsión Social (IPS). This works out at about 1.6 formal jobs per MW of energy. A more traditional industry like textiles, critics suggest, would employ hundreds more people per megawatt.

As well as concerns over noise pollution and energy usage, Paraguay is about to face a tsunami of bitcoin basura. Old mining machines (ASICs) are frequently chucked away when they become obsolete. Back-of-napkin estimates put the total number of ASICs in Paraguay at about 100,000.

With no meaningful legislation or recycling system in place to manage electronic waste, that’s an awful lot of hardware that could end up in Paraguay’s rivers, fields, clandestine landfills, and on the streets.

Privately, mining executives say their companies offer quality – if not quantity – when it comes to jobs, providing highly skilled employment for software engineers, technicians and accountants. Many Paraguayan employees say they are well paid and treated compared to their peers in other professions.

Meanwhile, the tussle for the future of Paraguay’s crypto landscape continues to unfold, from Villa Morra to Paraguay’s congress to Toronto.

Back in Villarrica, Arrúa believes there could be a silver lining to the noise dispute if the community is given the opportunity to get involved in the new industry on their doorstep.

“We’re the ones living alongside crypto,” she says, “so we are the most invested in ensuring this situation benefits us rather than harms us.”

Sam Meeson-Frizelle is a digital anthropologist studying cryptocurrency mining in Paraguay.