Paraguay’s Bolt and Uber Uprising

Faced with danger and precarity, drivers are organising.

In February 2024, a message reverberated through a radio channel used by Kuña Pope, an association of women who drive for apps like Uber, Bolt and MUV in Asunción, Paraguay’s capital: “Girls, they just tried to rape me.”

“Seven of us drivers who were online rushed to her. First, we went in a few cars to try and track down the attacker. We couldn’t find him, so then we went together to the police station to file a report,” says Leticia Vargas, the group’s president.

Kuña Pope – meaning “In Women’s Hands” in Guaraní, the native language widely spoken in Paraguay – was formed six months earlier, after a murder of a male driver while on shift prompted his female colleagues to take steps to protect each other.

After last year’s attempted assault, the authorities said there was insufficient evidence to take the case forward. But the group of women drivers wasn’t beaten.

“We realised that we had to do something, so we began to investigate,” Vargas tells The Paraguay Post.

They soon discovered that the same man had already assaulted two other drivers using the same modus operandi: luring them to a remote plantation of pine trees in Villa Elisa, on the outskirts of the city. After three weeks on alert, one of Kuña Pope’s drivers received a similar request.

She called for backup. A posse of male and female drivers went to hide out at the location. When their car pulled up, the attacker was already threatening her with a knife. Together, the vigilantes dragged him from his car and detained him, filming the scene as evidence.

Bolt from the blue

The episode highlights the risks facing drivers – both male and female – in Paraguay’s burgeoning ride-sharing industry.

The sector has exploded in popularity since home-grown app MUV and US ride-hailing giant Uber set up shop in Asunción in 2018.

Tired of braving the capital’s dilapidated, delayed and overstuffed buses – or unable to afford their own vehicles – asuncenos embraced the ability to summon a lift to work, university, and social engagements from the palm of their hand.

The pandemic provided another boost for the apps. Just as thousands found themselves without work, a low-cost competitor appeared in 2020. Bolt offered zero percent commission for drivers, fares a fifth cheaper than the competition, and required practically zero checks to create an account: either as a driver or passenger.

The Estonian firm – which operates in 600 cities worldwide, mainly in Africa, Asia and Europe – has since dominated the streets.

Despite a host of robberies and assaults reported by users on both ends, and hefty hikes in the commission charged on each fare, Bolt is still preferred by the majority of drivers. In 2024, Bolt indicated that it has 15,000 active drivers in Paraguay, two-thirds of them in the greater Asunción area.

Uber tends to be safer, but is less in demand, and can skim anywhere between 20 and 60 percent off the top of a ride. MUV, meanwhile, has mainly found a niche in the corporate world thanks to its automatic emission of tax-deductible receipts.

Yet despite the growing ubiquity of the taxi apps, Paraguay’s government has no official data on how many drivers there are or the gig driving economy as a whole.

Partners or workers?

The apps style themselves as technological intermediaries that merely link passengers with drivers, who in turn operate as “independent partners.”

Several drivers interviewed by the Post said they valued the opportunity to earn money quickly and work when they chose. Some were otherwise unemployed; others were housewives, retirees, and low-wage workers. One even said they were “looking for an alternative to selling drugs.”

One driver, Mariela, started out driving by necessity. But she’s since embraced the chance to meet people from all backgrounds, and is turning the fleeting encounters into material for her first book: Memorias de una conductora de plataformas, or Memoirs of an App Driver.

Most said they netted between 20,000 and 30,000 guaraníes ($2.50 to $3.75) per hour, after commission. Nearly 90 percent of drivers earn between 2.2m and 3.3 guaraníes per month ($280 to $414) working 48 hours a week: roughly equal to Paraguay’s minimum wage of 2.8m guaraníes.

But drivers also need to pay for fuel, maintenance, and insurance, and often rent their vehicle. Several confessed that – despite the promises of empowerment offered by the apps – they were struggling to stay safe and make ends meet.

Not only are stick-ups and scams an occupational hazard. Between 2023-24 alone, 18 ride-hailing drivers were murdered in Paraguay.

A social solidarity network

In response, a dense support network has flourished online.

Some drivers have marked streets where robberies often take place on Google Maps, and use GPS navigation app Waze to indicate the presence of police controls and potholes.

Members of the WhatsApp group “Conductores en la Noche”, or Night Drivers, have created their own code of alerts on Waze to notify each other of danger, accidents, and emergencies.

“When someone gets a puncture or their battery runs flat, we help them out,” says one member. They share jokes, news, and get into debates to stay awake while waiting for fares in the early hours. The group recently agreed to collect a monthly contribution towards a mutual sick pay fund.

Some members are exploring the option of forming a cooperative: circumventing their current lack of formal employee status or earnings, without which it can be difficult to secure loans to buy their own vehicles.

Facebook, Instagram and TikTok are also used to share information about how to avoid scams, and strategies to recover accounts. The apps can often block drivers simply for refusing journeys or receiving a poor rating, leaving them without work for months.

Drivers also use social media to organise protests and temporary boycotts of the apps. The latest, in early May, protested a hike in the commission taken by Bolt from 15 to 20 percent without prior warning. Another such demonstration is planned for June 10.

To unionise or not to unionise

Paraguay’s Uber, MUV and Bolt workforce are increasingly interested “in organising themselves informally, but not unionising,” says Eduardo Carrillo, a consultant with TEDIC, a Paraguayan digital rights NGO.

Partly reflecting the weakness of organised labour, such traditions of self-help are deeply rooted in Paraguay. Just one percent of private-sector workers belong to a union: one of Latin America’s lowest rates.

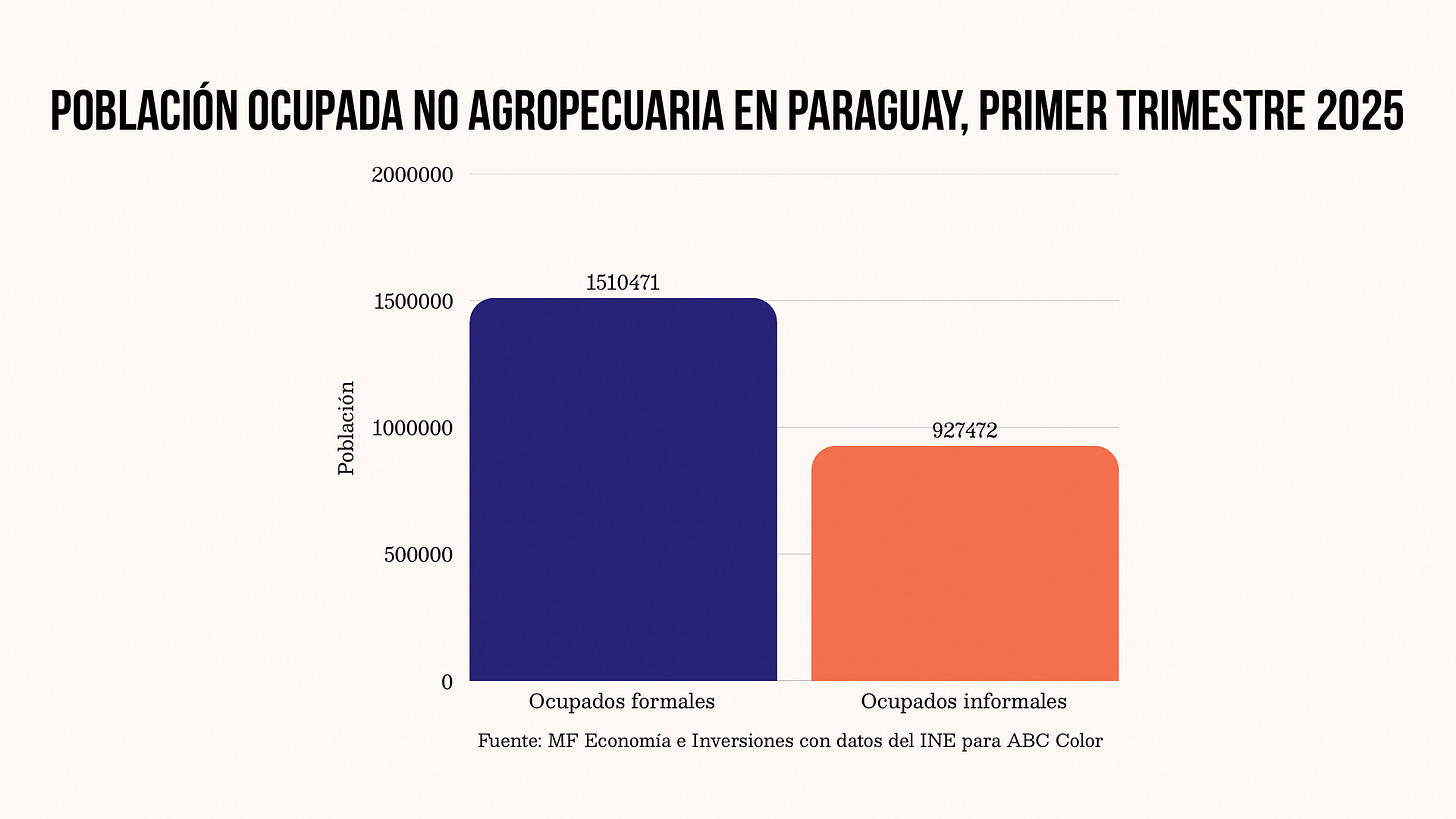

Then there’s the country’s high rates of informality, with 65 percent of the economically active population working without a contract and health insurance, according to official data.

Against this backdrop, many drivers welcome the prospect of being an independent “partner”. Some fear that, under a formalised employer-employee relationship, they will lose the freedom to pick their hours, work with multiple apps, and pull extra-long shifts to earn more money.

Others suspect that the multi-million dollar tech companies will block their accounts if they seek to unionise.

Yet a growing group is seeking recognition as workers with rights: including the capacity to formally negotiate conditions, receive protection from having their accounts arbitrarily banned, earn employer contributions towards their pensions, and receive sick pay.

Fighting the algorithm

“The platforms don’t take into account traffic when they calculate fares,” one driver tells the Post. “When there are bottlenecks, you lose fuel and time … they even penalise you for taking longer than expected.” He says that repeated attempts to raise this issue with Uber have met with no response.

Vargas, the president of Kuña Pope, says that many have come to doubt the notion that drivers are really in control of their hours.

“For months, I felt like my routine was being guided by the logic of a video game,” she reflects. “The app rewarded me if I worked more, especially during the hours that it wanted, and it punished me if I rejected journeys or logged off. I ended up adapting to its rules without realising it.”

“We’re facing a clear situation of subordination and dependency,” says Carrillo, the expert with TEDIC. “The existence of these networks of solidarity between drivers is just another symptom of their vulnerability before the ride-sharing platforms.”

“There’s a need to sit down, better understand the situation facing the drivers, and on the basis of that build a regulatory model that works for everyone,” he adds.

Last month, TEDIC hosted representatives from eight countries across the region to jointly draft the Asunción Declaration on Platform Work in Latin America.

The document makes several recommendations for public policies to guarantee human dignity under this new model of work that – taking into account food-delivery workers for apps like Rappi and Paraguayan equivalent Monchis – is estimated to employ tens of millions of people worldwide, especially in the Global South.

Safety first?

Faced with protests, the ride-sharing companies have gradually introduced some improvements, including an emergency button in the Bolt app that dials 911.

Bolt has also created a position tasked with liaising with drivers and their associations. In April, the Tallinn-headquartered company held a “Safety Summit” with drivers and local authorities in Asunción.

Country manager Fernando Barzoza told attendees that “safety is not just another function” of Bolt but “the central focus of our operation,” announcing a €100m ($114m) investment in improving the driver and passenger experience worldwide.

Drivers remain skeptical. “You can’t imagine everything they’ve promised us,” says Vargas. “Bolt’s representatives say they are listening to us, but all they can do is relay our concerns to Estonia.”

While the company seems more open to dialogue, changes typically take “years” to materialise, Vargas adds. “Meanwhile, we’re the ones exposed to the risks in the streets.”