Paraguay’s Forest Guardians Are Under Fire

Narcotraffickers threaten a unique ecosystem. How can it be saved?

Rangers at the Reserva Natural del Bosque Mbaracayú – a sprawling forest tucked into Paraguay’s eastern border with Brazil – wear uniforms printed with their blood type in case they end up taking a bullet for Mother Nature.

“The reserve is dying,” says Diego, a stocky guardaparque with a handgun strapped to his thigh, leading a group of visitors to a 40-metre waterfall in a pristine jungle valley. “There’s a beautiful energy here. But not everybody feels the same way.”

He points out a freshly-cut trail that leads to marijuana plantations carved deep inside the sub-tropical forest earlier this year.

“It’s growing too fast,” Diego – not his real name – told The Paraguay Post. “It’s hard to control.”

Diego, like his other colleagues, regularly finds himself in shootouts.

“We’re risking our lives,” explains the forest ranger, one of 23 tasked with guarding nearly 250 square miles of the reserve. He earns minimum wage plus a danger bonus, adding up to roughly 3,330,000 guaraníes ($420) per month.

“If they can’t get at you, they target your family,” the Diego reflects. “But if we don’t take a stand, things will keep getting worse.”

The last refuge

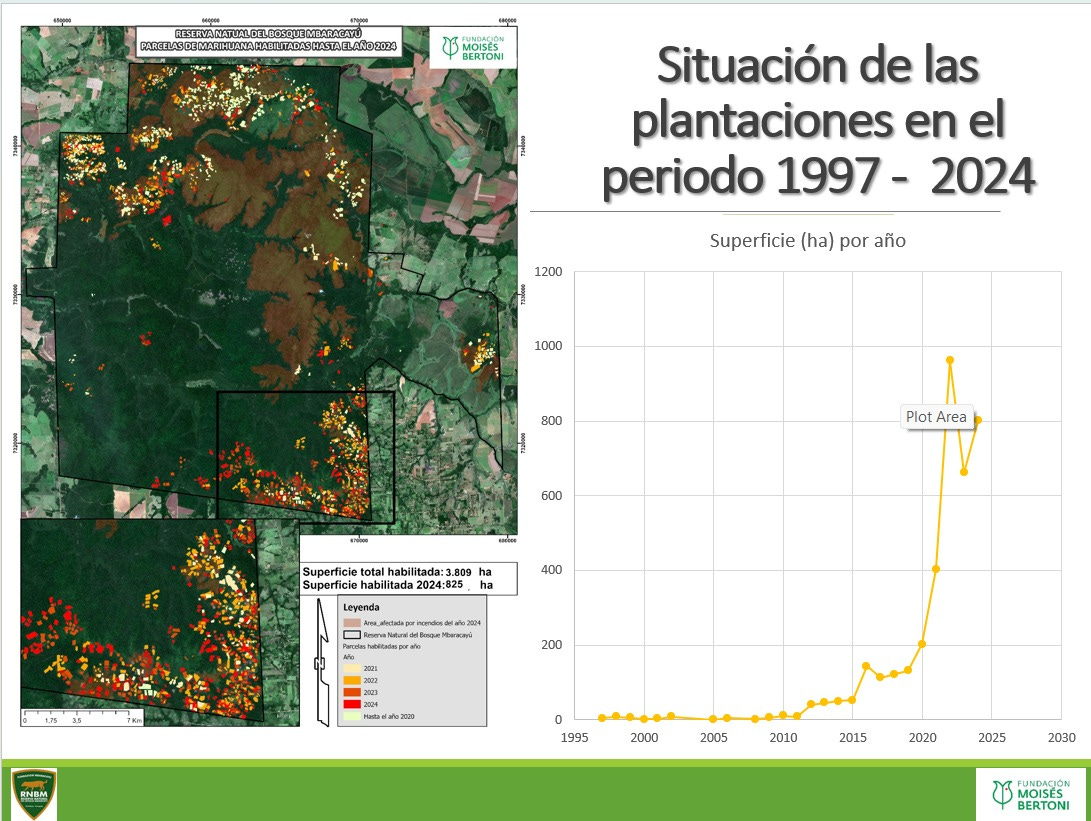

On satellite images, the Bosque Mbaracayú – a little over 64,000 hectares of lush vegetation, corkscrewing rivers, and biodiverse cerrado savannah – stands out as a dark block of green among the patchwork farmbelt of Canindeyú.

Created by law in June 1991 – and managed by the Fundación Moisés Bertoni (FMB), a Paraguayan NGO – the private reserve is one of the last surviving fragments of the dense Atlantic Forest that once cloaked swathes of South America.

Yvyra pytã trees, some two centuries old, are slung with creepers like a grandmother in her Sunday rosaries. It would take three people to link arms around their maroon, moss-dappled trunks.

The canopy is punctured by pale giants known to the local Aché people as ka’i kyhyjeha – monkey-frighteners – for their slippery trunks.

Scientists say the Atlantic Forest remains a global hotspot for wildlife, with many plants and animals found nowhere else on the planet.

Electric-blue butterflies shimmer in shafts of sunlight. Fungi shine like snowfall amid the understory. The treetops are known to echo with the metallic chirrup of the pájaro campana, Paraguay’s national bird. Camera traps have recently registered 11 jaguars and their cubs.

By capturing rainfall and moisture from the atmosphere, the Atlantic Forest is also crucial for topping up the region’s aquifers and rivers – and even powering the Itaipu hydroelectric dam.

Yet Paraguay’s portion of the ecosystem, including the Bosque Mbaracayú, boasts a grim triple distinction. It’s uniquely biodiverse, seriously understudied – and in severe peril.

The department of Canindeyú has lost half of its primary forest since the turn of the millennium: mainly at the hands of cattle ranchers and farmers.

Diego, the ranger, was once one of them. Six years ago, he was atop a tractor tearing down vegetation for a soybean baron. The temperature in the fields was 40 degrees Celsius. Under the trees, it was cooler.

“You feel like nature is providing you with something, and you’re destroying it,” he recalls. “It was then I realised that I want to protect all of this. We have to do something, and do it now.”

But with destruction by agribusiness having slowed in Paraguay’s eastern region – partly thanks to legislation known as the “zero-deforestation” law enacted in 2004 – attention is shifting to the weed growers.

In recent years, Paraguay has legalised cannabis production for industrial, medicinal and scientific purposes, but unlicensed growers risk jail.

And this illegally-grown crop, of which Paraguay is South America’s biggest producer, is steadily eating away at the forest from within.

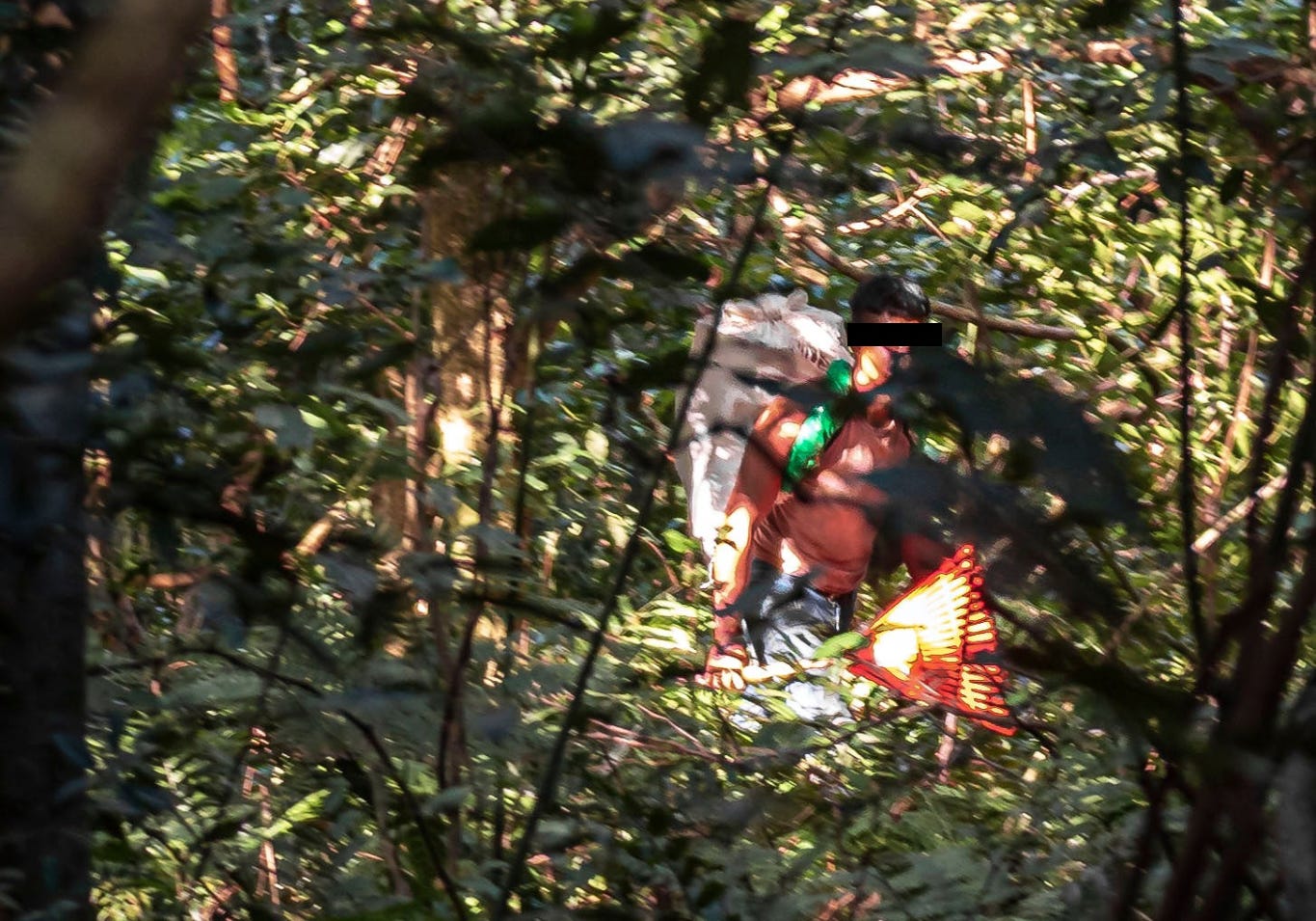

The growers are often Indigenous and campesino locals hired by transnational drug gangs, in turn protected by local political elites. “They're our neighbours,” says Diego. “We know who they are.”

“They’re being used. Sometimes they go there to work and don’t get paid,” he adds. “If they speak up, they’re killed.”

“Sometimes we detain them, take them to the police station, and the prosecutors and judges are paid off. Within 15 days, they walk free.”

Joining them, he adds, are new arrivals from the next-door department of Amambay, ground-zero of Paraguay’s illegal weed business. “There’s no more space to plant, there’s too much soybean. So people are coming here.”

Sacred energy

Margarita Mbywangi – wrapped in shawls against the morning chill, and perched next to a smoky hearth in her earthen-floored kitchen – doesn’t look like a typical government official.

But in 2009, she briefly served as Paraguay’s Minister for Indigenous Affairs. And here, in the Aché community of Kuetuvy, she is also on the front lines of the fight to defend the Bosque Mbaracayú.

“For us, the forest is sacred,” says Mbywangi, a 62-year-old grandmother of ten. “It hurts us too much that it’s being destroyed.”

As a child, Aché elders told her how their people had once hunted and foraged across a vast, tree-covered territory. “We roamed from here to Brazil. They said that they could see the big water, the ocean, the ships that passed,” Mbywangi recalls.

But Alfredo Stroessner’s 1954-89 dictatorship subjected the Aché to a genocide. Aged six, Mbywangi was enslaved by a Paraguayan family. It would be ten years before she could escape and return to her community, where she struggled to fit in.

“I had a really tough time,” explains Mbywangi, now a respected leader. “But that helped me to be strong. Because I had made a promise, a vow, to help my people.”

Today, the Aché only dare enter the forest in large groups out of fear of the drug gangs. “You’re afraid to run into those people,” she explains, “because they’re heartless.”

In recent years, fires set by the marijuana growers have almost consumed the community. After Mbywangi reported the deforestation, she also received death threats.

“We have no protection,” she says. “They could come and kill us at any time.”

In 2013, her nephew Bruno Chevugi – an Aché ranger employed by the Moisés Bertoni foundation – was shot dead while patrolling the reserve. His killers were never identified.

But Kuetuvy continues to resist: reforesting its territory, lobbying the state. “We’re in the struggle, bothering pretty much everyone,” Mbywangi chuckles.

The village has also developed an unlikely alliance with a Californian beverages company. Since 2002, Kuetuvy has cultivated 61 hectares of yerba mate bushes, exporting the leaves for use in teas and energy drinks made by Yerba Madre.

Mbywangi proudly shows the Post around a sustainable organic plantation, cultivated beneath the canopy in harmony with the forest. “We use the money here for healthcare, electricity, water, for the processing plants, for our schools, everything.”

She admits that some of her neighbours have become ensnared in the marijuana business, but only on its lowest rung.

“They plant because the government isn’t here,” she argues.

The school of nature

Elida Gómez, the reserve’s only female guardaparque, is also trying to turn the tide.

In 2012, she was among the first cohort to graduate from a unique boarding school created by the Moisés Bertoni foundation within the forest.

The Centro Educativo Mbaracayú (CEM) caters exclusively to young women. Indigenous girls study for free.

If it weren’t for the CEM, says Gómez, “I’d still be in my hometown, working in a supermarket or as a cleaner. The school has really helped so many girls.”

“We’re being trained to be future leaders in sustainable development,” says Luna, 16, giving the Post a tour.

For some, the school represents the first time they have been asked a simple question: what do they want to do with their lives?

“I haven’t worked it out yet,” admits Luna, who grew up in Canindeyú, “but I’m really drawn to artificial intelligence and robotics.”

“The CEM is a conservation strategy,” explains Palmira Mereles, 31, the school’s director, and another graduate of its first intake.

By giving local families a stake in the reserve, the hope is they’ll help protect it. As Luna puts it: “Who’s going to want to destroy their children’s home?”

Pupils also get work experience, learning agroecology and catering for guests at the foundation’s hotel next door – the Mbaracayú Lodge – which offers canoeing, community tourism, and guided walks.

But even in this oasis, some are worried. The reserve – says one FMB employee – “is like an island, but it’s increasingly under attack.”

Development through security?

The government’s main response to the ecological and social emergency in Canindeyú has been to militarise the department.

The area around the forest is now host to a panoply of armed groups: official and irregular, real and rumoured.

Gun-toting private security guards. Gangs warring over weed plantations and clandestine airstrips used by cocaine-laden planes from Bolivia. Troops from Curuguaty, the regional capital. The SENAD, Paraguay’s anti-drug force.

“If there’s no security, there can be no development,” argued Paraguay’s president, Santiago Peña, announcing the deployment of the Fuerza de Tarea Conjunta (FTC) in April 2024.

This May, after a rural police station came under attack, the task force’s spokesman suggested that the EPP armed group could now be active in Canindeyú and may hide out in the Mbaracayú Reserve.

Locals are skeptical. “Even I find it hard in the forest,” says Mbywangi. “I can stand two or three days before I want to get out.”

Diego says that the backup is welcome, but it will take years to have a lasting impact. And the underlying causes of criminality and deforestation are likely to remain.

Staff at the Asunción head office of the foundation – named after Swiss botanist Moisés Bertoni – say only six percent of the Bosque Mbaracayú, or some 3,800 hectares, have been deforested in the past 20 years. An area six times the size of Paraguay’s capital remains untouched.

Some of the FMB’s programmes elsewhere in Paraguay have been affected by Donald Trump’s cuts to foreign aid, but it says financing for the reserve ultimately derives from carbon credits.

And it emphasises that it provides its rangers with training and equipment, and seeks to keep them out of harm’s way.

Yet the murders of guardaparques like Bruno Chevugi clearly weigh heavy on Diego.

Preserving the natural haven, the forest protector insists, “is not an impossible task. It’s possible. But it’s difficult.”

Rethinking prohibition

Retracing our steps from the waterfall, The Paraguay Post runs into two boys carrying bulging canvas sacks, seemingly headed for the plantations. They look around 10 and 15, at most.

Diego questions the elder of the two in Guaraní. “Moõ reho? Where are you going? Entering here is forbidden.” After a momentary stand-off, they notice his hand hovering over his pistol, and run for it.

“They’re Indigenous kids,” says Diego. “You can see they’re not armed. But sometimes they carry knives.”

“I feel sorry to see situations like this,” he adds. “I’d like to talk with people to find a solution: helping local communities, investing in people, giving them dignified work.”

“Why doesn’t the government legalise this plant, if it grows so well in Paraguay?” asks Mbywangi.

“I don’t want to see any more of my friends and neighbours die,” the Aché elder adds. “Why should someone’s life be taken away for such a small thing?”

Additional reporting: Giuliana Meilicke

Editing: Daniel Duarte and Norma Flores Allende

Visual editing: Isabela Marini

Photography: Matteo Fabi

This investigation was supported by Periodismo Por La Acción Climática, an initiative by Agencia Global de Noticias, Emancipa Paraguay, and El Surtidor with backing from WWF Paraguay and Fundación Avina.