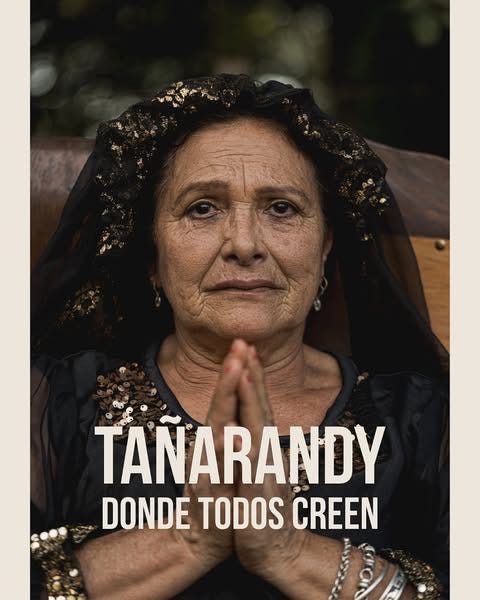

Tañarandy Makes Believers of Us All

Two visitors are caught up in a Good Friday like no other.

Photography by Rut Ortiz Montenegro.

Tañarandy, a Holy Week festival on the outskirts of San Ignacio, Misiones, is more than a religious experience: it’s a communal artistic endeavour, a spiritual sensation, and a meeting of powerful (and even extraterrestrial) energies.

Begun more than 30 years ago by the sculptor and cultural curator Koki Ruiz (1957-2024), Tañarandy – held in a rural community of the same name – has since become a living spectacle that everyone who finds themselves in Paraguay should witness.

This year’s reenactment of the Passion, crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus was a homage to the late artist by his children – Macarena, Almudena, Julián and Eduardo – his widow, Norma Fretes, and San Ignacio as a whole.

“My father loved to create spaces where people weren’t just onlookers but could participate, live the experience, and feel the emotion,” Julián tells The Paraguay Post. “And that was exactly what happened. The response from the community was, without doubt, one of the greatest gifts this year’s event could have given us.”

Set aside your own beliefs, the god(s) you worship, your spiritual practice or your agnosticism. When you set foot in the territory of Tañarandy, all skepticism vanishes. Their air feels charged with meaning, a feeling that reaches fever pitch after 7 p.m on Good Friday.

Last month, we were among the thousands of people who traveled the 140 miles from Asunción – along with many from points more distant – to Tañarandy. Our purpose was not to witness the death of Jesus but the life of a community, the collective labour of artists and artisans, a history cast in clay.

But this year was different: it was the first time the festival has taken place without its founder being present, at least in physical form.

Larger than life

Delfín Roque “Koki” Ruiz Pérez was born and developed his artistic practice almost entirely in San Ignacio. A self-taught painter who also studied architecture in Brazil, once back in Paraguay he experimented with natural materials to better depict the countryside.

He began to work on a bigger scale than just canvas, designing and making scenery for local plays and staging community theatre projects: chief among them Tañarandy and El Molino. Everything he did, says Julián, was driven by a deep conviction in the need to “keep alive the cultural and religious roots of his community.”

Koki began to exhibit his work in Asunción and abroad, but was drawn back to rural Misiones with the mission of creating something transcendental. “While many stayed in the capital in search of prestige, he returned to his hometown to paint his land, to work with its people, and to leave a mark,” Julián explains.

Today, Tañarandy’s identity is simultaneously religious, mystical, and folkloric. Bible stories are mixed in with urban legends of UFOs and the eccentricities and obsessions of local families. Each house along the sandy track that leads to San Ignacio is adorned with lettering spelling out the family surname and their role in the community. Then there’s the billboard marking out calle Amorcito, lover’s lane, where couples go to canoodle. Or the famous mural of a flying saucer descending to a warm welcome in 1998.

There are tales for all tastes and creeds. And, even if you try to remain a detached observer, there comes a moment when the atmosphere shifts, and the mournful singing of the of estacioneros marks the beginning of the ritual: the procession of the Virgen Dolorosa, our Lady of Sorrows. Kids, teenagers and elderly choristers shuffle between the stations of the cross and raise their voices to the heavens, turning a shade of lavender as dusk begins to fall.

Along the route of the procession towards the lakeside, where the central spectacle unfolds, a stretch of the lane is strewn with home-made candles stuck in the rinds of bitter apepu oranges. Some people have got jittery and burned through their wicks already; others are more patient. But they too now scramble to borrow a flame, because the Virgin is coming. “Pay attention when you light your candle,” a woman, solemn and visibly moved, confides in us, “Because a revelation should come to you.”

Suddenly, the whole path is lit up with oranges, torches, and lanterns. The fire dances at your feet, at peoples’ hands, in the air. The smell of citrus smothers those two miles it takes to reach the lake. We form part of the spectacle, the ritual. Something is being invoked. Meanwhile, lightning strikes, far off in open ground.

We hurry to reach the waterside before the procession, because that’s when the living paintings take form. The natural amphitheatre is full: a football stadium stuffed with fans of Jesus, Koki, or tradition. The sharper old ladies from the area have long since been installed in their folding chairs. We inexperienced city folk have to squeeze through the masses and squelch through the mud to find a spot to spectate from.

Just when, breathless, we’re on the point of giving up, we find a spot to dig in. Finally we see the Virgin arrive, and Jesus descending from the cross.

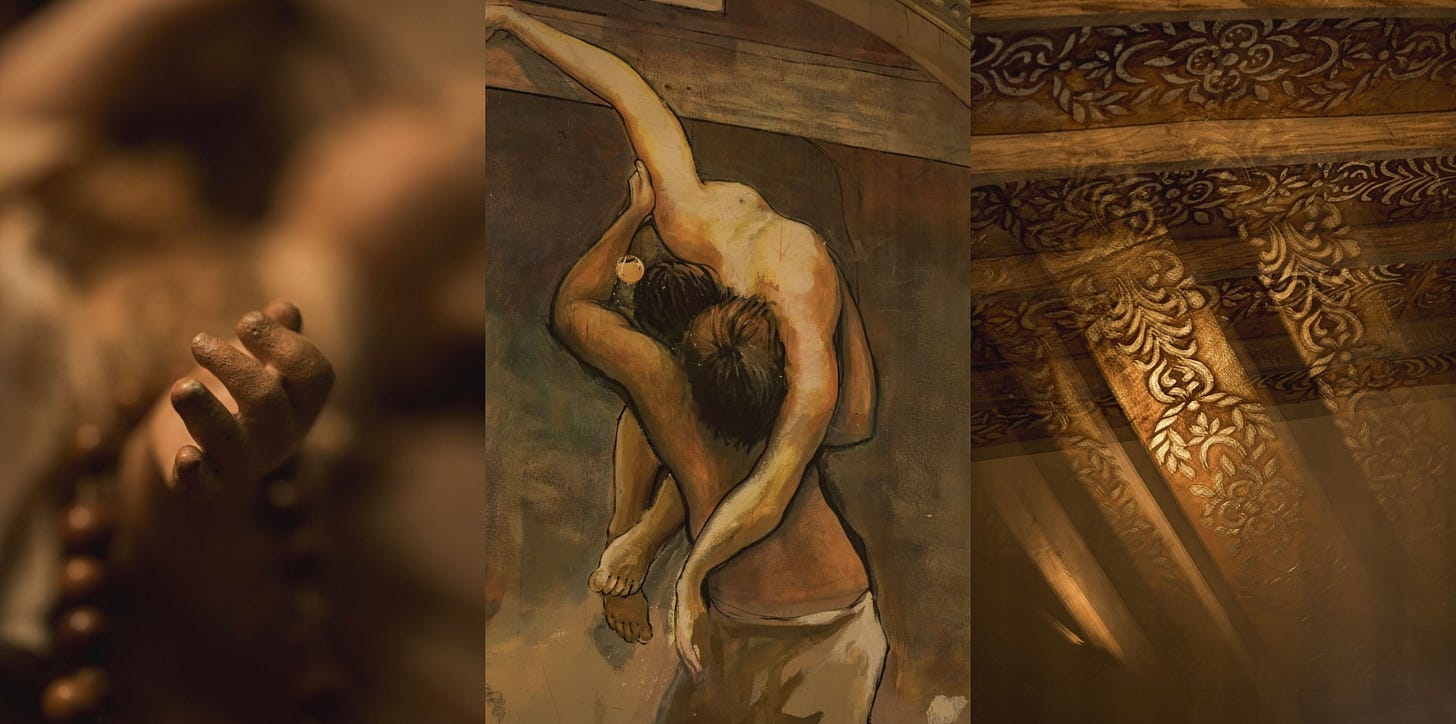

Paintings that live and breathe

One of the night’s most moving moments was the speech given by Julián, who with his siblings led the organisation of the event, which takes months of preparation by more than 100 people. Almost choked with emotion, Julián said that continuing with the tradition is what his father would have wanted, and that although Koki was no longer around, they felt his presence.

He explained details about each of the paintings that local actors, frozen stock-still, were taking it in turns to embody. The theme was The Last Supper, because the famous Da Vinci composition was Koki’s favourite. “Although dad sometimes wanted to innovate with other paintings, he always returned to this one, because of the connection he felt with its subjects,” Julián added.

With a changing light display and a purpose-recorded soundtrack, we gaze on the classic encounter around the table, with a Jesus who cries in real-time surrounded by his apostles. Then the scene shifts to a contemporary, monochrome, Warhol-style scene where the disciples take their leave. There’s also La Piedad – La Crucifixión, an irreverent and hard-hitting image loaded with pain and dark symbols.

Finally, the Last Supper again appears: but this time refracted through Salvador Dalí, with Christ appearing only as a light in the middle. The disciples, Julián explains, are played by Koki’s close confidantes: “We wanted them to be part of this final homage, as an intimate and symbolic farewell.”

There are also two of Koki’s works on display which hold special meaning for the Ruiz family. On one side, the great retablo of San Francisco and San Ignacio, a towering altarpiece made of corn, coconuts and pumpkins created for Pope Francis’s visit to Paraguay in 2015. On the other, an altarpiece dedicated to Chiquitunga – a Paraguayan nun beatified by Francis in 2017 – made of 70,000 rosaries donated by the faithful.

For Julián, his father’s legacy is not only artistic, but also cultural, and lives on in the area. “It’s not about just his family carrying on what he started, but seeing how the whole community is making it their own.” His father’s biggest lesson, he says, is that great things can be achieved in common, for the common good: “That’s what drives everything we do.”

The show doesn’t last for long, but the impression remains on the retinas, in the body, in the spirit. The actors maintain their poses so the public can approach and see them up-close. From here, you can see that they’re not statues, but people, who have been rehearsing for months, or in some cases, years. You can see the faith in their eyes. Faith in something greater, something enduring that calls them to join the spectacle, whether art, collective endeavour, or the divine.

What’s clear is that, upon leaving, it feels absurd to maintain the fiction that we’re alone, that only individuals create masterpieces, or that art in its truest form can only be found in the grand and prestigious museums of this world.

Head to our Instagram to see more photos of Tañarandy by Rut Ortiz Montenegro.