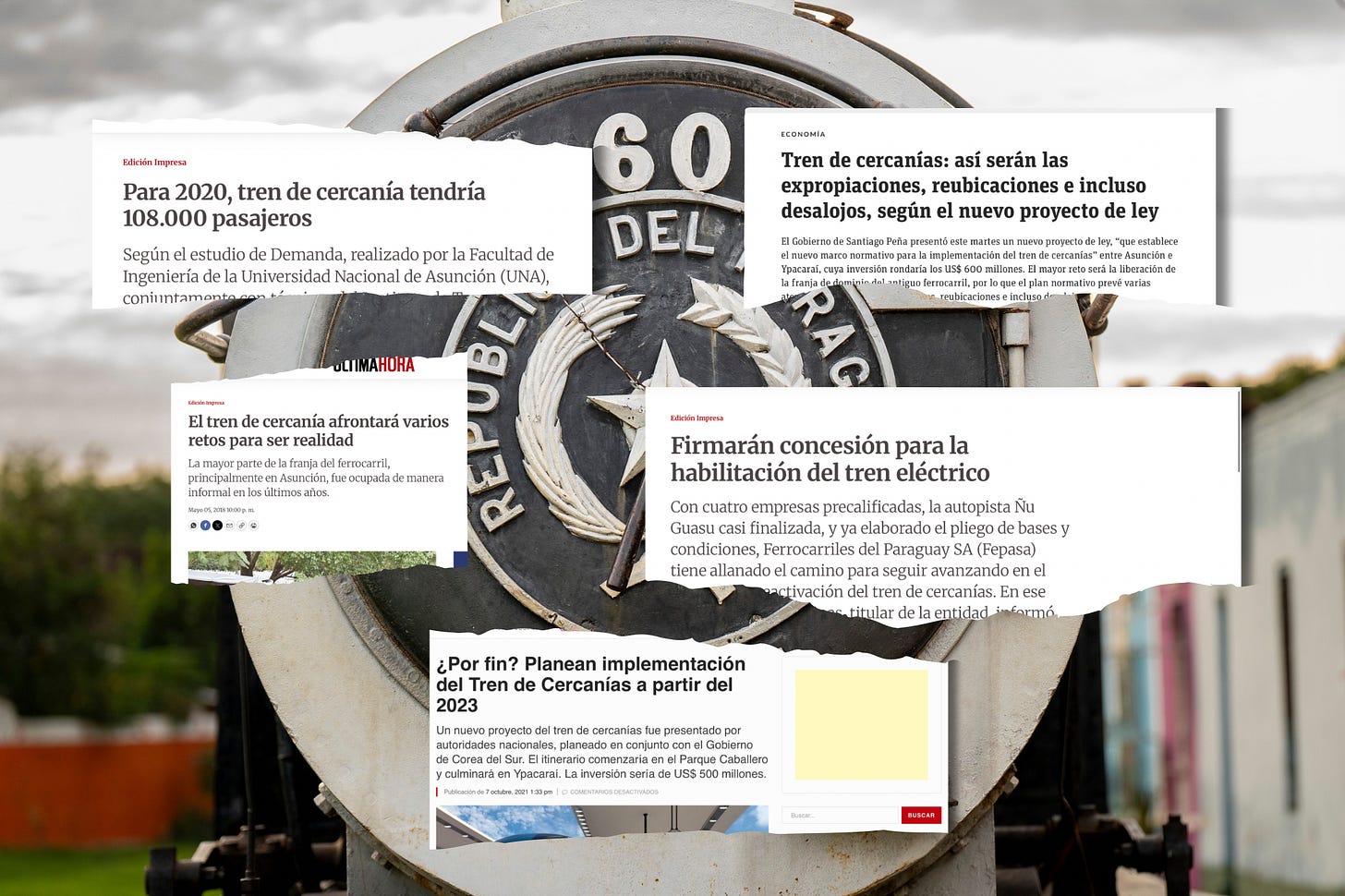

Back on Track? Paraguay’s Railway Revival Faces Delays

A planned commuter train in Asunción sparks nostalgia, hope — and skepticism.

Fepasa, Paraguay’s national rail company, has more than 30 employees, annual expenditures of over two billion guaraníes ($270,000) — and zero functioning trains.

It wasn’t always like this, says Guillermo Soria, a railwayman of nearly 40 years’ service, proudly showing The Paraguay Post around the faded Central Station in Asunción.

Starting in 1854, he explained, President Carlos Antonio López hired hundreds of British engineers to build one of South America’s first railways.

The steam trains linked isolated towns with the capital, inspired an exuberant polka on the harp — and triggered a burst of life when they chugged into the station.

“This place was full of vendors of all kinds, photographers, people selling chipa and trinkets,” recalls Soria, standing on an empty platform next to a stranded locomotive. “Then it started to lose its shine.”

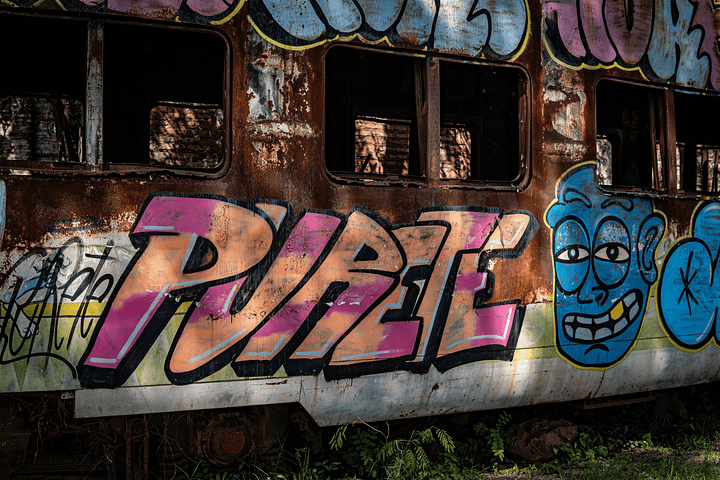

The era of the motorbike and the chilere — cheap second-hand cars — dawned. Trucks and container ships undercut the freight wagons. The Colorado Party starved the railway of resources. The Yacyretá dam submerged swathes of track.

Following two deadly derailments, the last wood-fired engines ground to a halt at the turn of the millennium. An eight-kilometre, cross-border diesel train linking Encarnación with Posadas, created in 2014, is owned by Argentina.

“We were left frozen in time,” Soria adds, unlocking a luxurious presidential wagon which once hosted Alfredo Stroessner and Juan Carlos I of Spain. “You could still use this.”

Paraguay’s current president has signalled that his nation will soon return to the rails.

Santiago Peña has repeatedly promised — including this month in his annual report to congress — to deliver a 43-kilometre passenger rail service connecting Asunción with Luque, Areguá and Ypacaraí.

“The Suburban Train will be fast, comfortable and safe, and help to ease the traffic,” he said, unveiling the project in December 2023. “We will improve the quality of life of 500,000 Paraguayans.”

“It’s our dream to have rail transport again,” grins Soria, 64. Over 200 households have already been relocated from the tracks.

But critics have questioned where the expertise and half a billion dollars needed to build the Tren de Cercanías will come from — and whether Peña, notorious for commuting to work via helicopter, is really invested.

To find out if the project stands a chance of becoming reality, the Post set out to follow the path of Paraguay’s once-and-future railway.

We encountered wistfulness for the railway’s golden age, bitterness after decades of empty promises — and cautious hope that the whistle might one day sound again.

Full steam ahead?

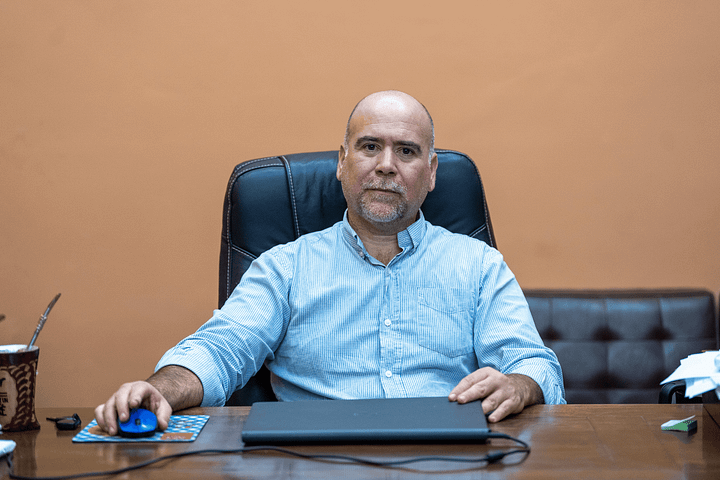

Seated in his office to the rear of the station, Facundo Salinas has no time for nostalgia.

“We should honour our history, but we can’t be anchored to the past,” he argues. “A transport company without any transport doesn’t make any sense. It’s madness.”

Peña plucked Salinas, an expert in infrastructure finance, from the finance ministry in August 2023 to head up Fepasa — and deliver the train.

Various presidents have talked up the rail project for 15 years, he continues, but Peña really means it: “That’s why I’m here.”

The rail chief says the double-track light electric railway will leave the Central Station and follow the route of the old steam train, with a viaduct between Avenida Peru and Avenida Sacramento reducing the need for further evictions.

South Korea is no longer helping to build the train — Salinas blames the falling-out on Seoul — but the project is receiving advice from Madrid and Santiago, Chile.

The contract to build it, estimated to cost $600m, will supposedly be put out for bidding in the second half of 2025. Foreign companies will have to partner with local firms. Paraguay will front $150m and pay the rest over 35 years.

Salinas predicts construction will begin in late 2026 and the first trains will be running by 2030: or earlier, if a “trial phase” to Luque is approved first.

“Poetry and literature are all well and good, but we need to deliver,” he argues, adding that a separate cargo rail project is under consideration. “We can’t keep wasting time.”

There’s not much poetry in the first few blocks of our journey. A man stirs inside a makeshift tent beneath the graffiti-covered locomotive marooned on Calle Gondra. A rooster pecks outside the railway depot beside Parque Caballero.

The Post peers in: there’s a few clapboard dwellings and a speedboat. A passerby recommends we keep moving: “You’re going to get robbed.”

A little further on, the tracks are hemmed in by duplexes and the stadium of Club Libertad. We find Bienvenida Francisca Jara selling herbal remedies outside her humble home a metre from the rails.

Jara, 59, remembers racing to bring in her laundry when the whistle sounded, and her furniture rattling when the steam train passed.

“If you don’t get your clothing inside, the cinders leave it like a colander,” she laughs. She wants the train back — she once used it to make a pilgrimage to Caacupé — but doubts it will happen.

“There are lots of buildings on the track,” she notes. And Paraguay’s authorities, she continues, “often get the money and use it on other things.”

Road or rail?

We detour onto Avenida Artigas — circumventing the collapsed bridge across the Arroyo Mburicao — before rejoining the rails in Trinidad.

Estación Botánico, overgrown with weeds, is today cut off from the eponymous gardens by six lanes of roaring traffic. We’re met by Mauricio Maluff Masi, Gustavo Espínola and Griselda Yudice.

They’re members of OPAMA, an association of public transport users whose acronym in Guaraní also means “none left”: as if in time, money, or patience.

“The public transport system is in a death spiral,” says Maluff, 34, a philosophy professor.

Asunción’s smoke-belching Mercedes buses, run by 36 different companies, are increasingly ending up at the scrapyard. Commuters cram into the remaining vehicles like sardines in a can.

One recent World Bank study found 78 percent of daily trips in Paraguay’s capital are now made by car or motorcycle, compared to less than 7 percent by public transport.

After inching forward for hours along the broiling tarmac, drivers are left “hysterical and exhausted”, says Yudice, 43, a congressional advisor.

“If we had an efficient system of public transport,” she argues, “our quality of life would be completely different.”

But the trio are skeptical that the Colorados and their construction-boss cronies can kick their asphalt addiction.

In April, Peña announced a $180m raised highway project connecting Asunción with Luque and Highway PY02 — along the exact same route as the Tren de Cercanías.

According to Salinas of Fepasa, the two will complement each other. OPAMA has branded it the death of the rail project.

The railway has “immense” symbolic value for Paraguay’s national pride, notes Maluff. “Building a highway on top of the former railway is like trampling over that.”

“In Bolivia they have passenger trains, freight trains, and a cable car,” he adds. “Meanwhile, we’re being let down by the complete incapacity of the state.”

In 2023, OPAMA exposed a massive fraud scheme where bus drivers faked trips by tapping the same smartcard hundreds of times to claim billions of guaranies in subsidies.

“The answer is citizen organisation,” says Espínola, 35, a graduate student in computer sciences. “There’s lots to fight for still.”

A transport reform package presented to congress last week barely mentions the Tren de Cercanías.

A few days previously, finance minister Carlos Fernández Valdovinos told reporters he had “little faith” in the rail project: “It looks like we’ll have to take that one out.”

Before we move on, the Post checks Google Maps. The pin marking Estación Botánico reads No upcoming departures.

Pedal power

Continuing on foot would mean walking along the Autopista Ñu Guazú. To reach Luque via public transport would require riding the bus for two hours on a loop via Calle Última.

Instead, we opt to drive the short distance to the satellite city’s Plaza del Ferrocarril, where Jero Buman is waiting for us.

A 51-year-old filmmaker, Buman caught the bike bug while living in Washington D.C, where a friend took him on a 100-kilometre ride along a former train line.

An idea germinated: “I’d love to replicate this in Paraguay.”

In 2017, Buman set out on a week-long journey down the disused Carlos Antonio López line: crossing streams, hacking through thickets with a machete, and video-blogging his adventures for a growing following.

His organisation, Sendas PY, is now creating a 27-kilometre accessible bike route along the rails between Ypacaraí and Paraguarí: a pilot project for something much more ambitious.

“Paraguay could make the news for a positive reason,” he enthuses: “Creating the longest cycle path in South America.”

Buman says the 380-kilometre route to Encarnación could run alongside a revived train. Tourists could catch a ride to a picturesque pueblo, explore by bike — spending money in local businesses — before pedalling to the next destination.

And in Asunción, the area beneath the elevated tracks would become “a corridor where you can jog, walk or cycle to work or university.”

For Buman, Paraguay’s neglect of its railways mirrors something deeper: a lack of national self-confidence.

“We Paraguayans feel so tiny in Latin America. We feel like we’re not capable,” he laments. “But there’s so much potential.”

We bump over the rails in our car and leave the city limits, shadowing the curving old train route to reach our next stop at Yukyry.

The station is shuttered, its doors flecked with Colorado Party propaganda. We follow the sleepers on foot into a tunnel of vegetation before the mosquitoes force us back.

A cultural locomotive

A short while later, the jolt of cobbles — and a procession of porcelain pigs, superheroes, saints and aliens — heralds our arrival in Areguá.

Here, an arts collective called Estación A are repainting the old station ahead of an International Ceramics Convention.

Gabriela Frers, who helps coordinate the group, is nostalgic for the weekend tourist steam train that used to reach here from Asunción.

“We organised artistic receptions with fine arts exhibitions, performances, music … Once, the Maká came and performed all their ritual dances,” she adds. “We had a dance group, a harp school.”

Older artists remember how locals jumped aboard the daily long-distance arrivals to sell oranges, cigars and handicrafts, while potters dispatched their wares to buyers in Argentina.

“We want the train back. We miss it, we long for it,” explains Rogelia Romero, 75. “It powered our local economy. Since the train left, Areguá has become impoverished.”

Luna Aguilera, a 19-year-old art student, climbed aboard the steam train for the first time as a small child. “It was really exciting,” she recalls.

A revived passenger train would make it easier for her to reach her classes in Asunción. “I’d like to repeat that experience,” she adds, “only with a longer journey.”

We continue down the southern edge of Lago Ypacaraí, passing the dilapidated station at Patiño, the Hechizo de Amor motel, a Mormon summer camp, and a piki voley court next to the tracks.

In Ypacaraí, the park between the old platforms is fronted by bars and cafés riffing on the train theme: La Estación del Helado, El Vagón, Estación 70.

For the town’s festival in September, its steam locomotive, El Inglés, is briefly brought to life and made to chug a few hundred metres forwards and back again.

“A lot of folks come from Asunción to see it,” says Agostina Pereira, 57, whose shop sells empanadas next to the track.

Asked whether the electric train will reach here in her lifetime, she’s pessimistic.

“Nothing ever gets done properly here in Paraguay. Just like the Metrobus,” she says, meaning an emblematic Asunción transit project that ground to a halt in 2018.

After nearly two years of traffic chaos, just 800 metres of bus lanes had been built of a planned 16km: at a cost of over $20m.

Signal failure

Pablo Callizo, a councillor in Asunción for the Patria Querida party, says the Tren de Cercanías project is sorely needed: but doubts Peña will make it happen.

“I don’t see a genuine decision by the government to push forward with the train,” he tells the Post. “It seems like every new administration wants to reinvent the wheel.”

“Lots of African countries have trains thanks to financing from China,” Callizo notes. “But we can’t get that, because we’re with Taiwan.”

Earlier this month, China and Brazil announced plans for a possible cargo railway linking the Pacific and Atlantic via Peru. If it goes ahead, it would undermine the case for a rival freight train project across Paraguay’s Chaco.

Paraguay’s population is too spread-out, and the distances involved too short, for a cross-country train to make sense beyond Ypacaraí, Callizo suggests.

But the councillor, a civil engineer, has sketched out proposals to connect the capital and its suburbs via trains, trams, ferries, buses — and even cable cars. Callizo’s proposal, ASUMETRO, comes with an estimated price tag of $1.4bn over thirty years.

By contrast, the lifetime concession cost of the expanded Ruta PY02 — the arterial highway which connects the capital with Ciudad del Este — is $1.7bn.

“With that, you could build three passenger railways in Asunción,” Callizo argues. “It’s a question of political will.”

In Ypacaraí, Victor Cabrera and Claudia Lutte, both 30, are soaking up the calm Saturday evening atmosphere outside the station with their two young children.

Lutte has to wake up at 4.30am to drive to work in Asunción, spending roughly six hours in traffic every day.

“We’re practically visitors to our own home,” she reflects. “The train would be fantastic.”

Soria, the ex-railwayman, even recalls with fondness how sparks from the boiler singed his skin.

If Paraguay could build a railway 150 years ago, he asks, “why not now?”